CARBOHYDRATES

The carbohydrates are a vast and diverse group of nutrients found in most foods. This group includes simple sugars (like the sugar you add to your morning coffee) and complex forms such as starches (contained in pasta, bread, cereal, and in some fruits and vegetables), which are broken down during digestion to produce simple sugars. The main function of the simple sugars and starches in the foods we eat is to deliver calories for energy. The simple sugar glucose is required to satisfy the energy needs of the brain, whereas our muscles use glucose for short-term bouts of activity. The liver and muscles also convert small amounts of the sugar and starch that we eat into a storage form called glycogen. After a long workout, muscle glycogen stores must be replenished. Both simple sugars and starches provide about 4 calories per gram (a gram is about the weight of a paper clip). Because carbohydrates serve primarily as sources of calories (and we can get calories from other macronutrients), no specific requirement has been set for them. But health experts agree that we should obtain most of our calories (about 60 percent) from carbohydrates. Our individual requirements depend on age, sex, size, and activity level. In contrast to the other carbohydrates, fiber (a substance contained in bran, fruits, vegetables, and legumes) is a type of complex carbohydrate that cannot be readily digested by our bodies. Even though it isn’t digested, fiber is essential to our health. Nutrition professionals recommend 25 to 30 grams of fiber daily.

Simple Sugars

Simple sugars make foods sweet. They are small molecules found in many foods and in many forms. Some simple sugars occur naturally in foods. For example, fructose is the sugar that naturally gives some fruits their sweet flavor. Table sugar, the sugar that we spoon onto our cereal and add to the cookies we bake, also called sucrose, is the most familiar simple sugar. A ring-shaped molecule of sucrose actually consists of a molecule of fructose chemically linked to a molecule of another simple sugar called glucose. Sugars such as fructose and glucose are known as monosaccharides, because of their single (mono) ring structure, whereas two-ringed sugars such as sucrose are known as disaccharides. Another disaccharide, lactose, the sugar that gives milk its slightly sweet taste, consists of glucose linked to yet another simple sugar called galactose. The inability to digest lactose to its constituent sugars is the cause of lactose intolerance, a condition common to adults of Asian, Mediterranean, and African ancestry. The table sugar that we purchase is processed from sugar cane or sugar beets. As an additive to many different types of prepared or processed foods, sucrose adds nutritive value (in the form of calories only), flavor, texture, and structure, while helping to retain moisture. Today, sucrose is most often used to sweeten (nondietetic) carbonated beverages and fruit drinks (other than juice), candy, pastries, cakes, cookies, and frozen desserts. One of the most commonly consumed forms of sugar is called high-fructose corn syrup. High-fructose corn syrup is also commonly used to sweeten sodas, fruit drinks (not juices), some ice creams, and some manufactured pastries and cookies. Other forms of sucrose include brown sugar, maple syrup, molasses, and turbinado (raw) sugar.

Foods that are high in added sugar are often low in essential nutrients such as vitamins and minerals. Unfortunately, these foods are often eaten in place of more nutrient-rich foods such as fruits, vegetables, and low-fat whole-grain products, and they may prevent us from obtaining essential nutrients and lead to weight gain.

Nutritionists are concerned by the enormous increase in sugar consumption by Americans during the past 30 years, particularly because much of this sugar is in the form of soft drinks. On average, teens today drink twice as much soda as milk, and young adults drink three times as much soda as milk. As a result, their intake of calcium-rich foods is low, a factor that is thought to contribute to lower bone mass. This can lead to an increased risk of bone problems as we grow older.

The increase in sugar consumption also has been attributed to the increasing availability of low-fat versions of such dessert and snack foods as cookies, cakes, and frozen desserts. Often, the sugar content of these foods is high because sugar is used to replace the flavor lost when the fat is decreased. Sugar promotes tooth decay, when consumed in forms that allow it to remain in contact with the teeth for extended periods (see sidebar: “Hidden” Sugar in Common Foods, this page).

Thus, foods that are high in sugar, or sugar and fat, and have few other nutrients to offer appear at the top of the Food Guide Pyramid because they should be eaten sparingly. In contrast, choosing fresh fruits, which are naturally sweetened with their own fructose, or low-fat yogurt, which contains lactose (natural milk sugar), allows us to get the vitamins and minerals contained in those foods as well as other food components that contribute to health but may not have yet been identified.

On the positive side, there is no credible evidence to demonstrate that sugar causes diabetes, attention deficithyperactivity disorder, depression, or hypoglycemia. No evidence has been found that sugar-containing foods are “addictive” in the true sense of the word, although many people report craving sweet foods, particularly those that are also high in fat.

Complex Carbohydrates

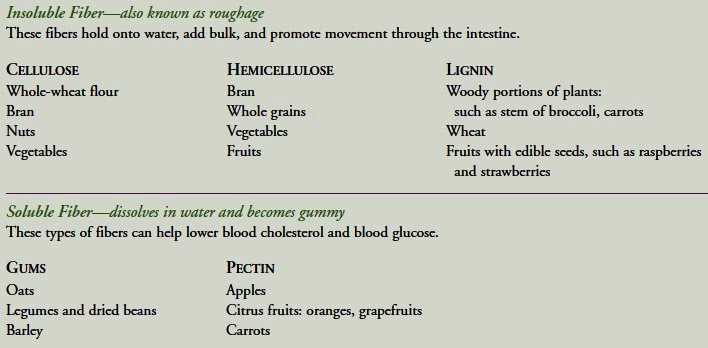

Found almost exclusively in foods of plant origin, complex carbohydrates are long chains of molecules of the simple sugar glucose. The complex carbohydrates in plant foods can be divided into two groups: starch and fiber. Starch is the form of carbohydrate that is found in grains, some fruits and vegetables, legumes, nuts, and seeds. It provides energy for newly sprouting plants. Fiber is the tougher material that forms the coat of a seed and other structural components of the plant. Starches are digested by our bodies into their constituent glucose molecules and used for energy, whereas fiber is not. Starch, like simple sugars, provides 4 calories per gram, whereas fiber(sometimes called nonnutritive fiber) provides no calories. Like simple sugars, the role of starches in our diets is mainly to provide energy. Fiber is actually a family of substances found in fruits, vegetables, legumes, and the outer layers of grains. Scientists divide fiber into two categories: those that do not dissolve in water (insoluble fiber) and those that do (soluble fiber). Insoluble fiber, also called roughage, includes cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin, found in vegetables, nuts, and some cereal grains. Soluble fibers include pectin, found in fruits, and gums, found in some grains and legumes. Fiber-rich diets, which include ample amounts of whole-grain foods, legumes, and fresh vegetables and fruits, have been linked with a lower risk of several diseases. Nutrition scientists are just beginning to understand the role of dietary fiber in maintaining health. Fiber appears to sweep the digestive system free of unwanted substances that could promote cancer and to maintain regularity and prevent disorders of the digestive tract. Fiber also provides a sense of fullness that may help reduce overeating and unwanted weight gain. Diets that are rich in fiber and complex carbohydrates have been associated with lower serum cholesterol and a lower risk for high blood pressure, coronary artery disease, and some types of cancer. But does this mean that it’s okay just to take a fiber pill? No! Rather, the studies that have shown the beneficial effects of a highfiber diet (containing 25 to 30 grams of fiber per day) have been those in which the dietary fiber is in the form of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and cereals. These and other studies suggest that not only the fiber in these foods but also the vitamins, minerals, and other compounds they contain contribute to their health-promoting effects. The Dietary Guidelines for Americans recommend that we obtain most (about 60%) of our calories from carbohydrates, preferably complex carbohydrates, in the form of foods such as whole grains, fruits, vegetables, and legumes. These foods are good sources of fiber, essential vitamins, minerals, and other phytochemicals and are also more likely to be low in fat. The average American today consumes only about a third of the recommended amount of fiber. To obtain as many of the potential benefits as possible, you need to obtain complex carbohydrates and fiber from various food sources. Although studies indicate that our intake of carbohydrates is increasing, the contribution of whole-grain foods remains small, partly because identifying whole-grain foods can be confusing. For ideas on what whole-grain foods to look for in your supermarket, see the sidebars Where Are the Whole Grains? and Finding Fiber, this page. Foods that are naturally good sources of fiber or have fiber added are allowed to make claims on their labels regarding their fiber content. What do the terms used to describe fiber content mean? When you see the phrase “high fiber” on a food label, it means that 1 serving (defined on the Nutrition Facts panel) of the food contains 5 grams of fiber or more per serving. A food that contains 2.5 to 4.9 grams of fiber in a serving is allowed to call itself a “good source” of fiber, and a food label that says “more fiber” or “added fiber” has at least 2.5 grams more fiber per serving.

“HIDDEN” SUGAR IN COMMON FOODS

Some foods contain sugar that has been added during processing. The following foods contain a large amount of sugar. The sugar content is shown in grams, and its equivalents in teaspoons are also given. Try to eat high-sugar foods less frequently or in smaller amounts. Check labels and compare similar foods-choose those that are lower in sugar content. Go easy on adding sugar to food.

Some foods contain sugar that has been added during processing. The following foods contain a large amount of sugar. The sugar content is shown in grams, and its equivalents in teaspoons are also given. Try to eat high-sugar foods less frequently or in smaller amounts. Check labels and compare similar foods-choose those that are lower in sugar content. Go easy on adding sugar to food.

The wheat kernel (or seed) consists of the fiber-rich outer bran layer; the inner endosperm, which is composed of starch, proteins, and B vitamins and is made into flour; and the germ, which is ground and sold as wheat germ, a rich source of vitamin E.

PLANT FIBERS: INSOLUBLE AND SOLUBLE

Sugar Substitutes

For the same reason that people have recently sought substitutes for fat, noncaloric sugar substitutes became popular in the 1960s as people began to try to control their weight. Sugar substitutes are of two basic types: intense sweeteners and sugar alcohols. Intense sweeteners are also called non-nutritive sweeteners, because they are so much sweeter than sugar that the small amounts needed to sweeten foods contribute virtually no calories to the foods. These sweeteners also do not promote tooth decay. Currently, four such intense sweeteners are available, both for use in processed foods and for home consumption. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has set “acceptable daily intakes” (ADI) for these sweeteners. The ADI is the amount that can be consumed daily over a lifetime without risk.

One of these sweeteners is aspartame (NutraSweet brand). It is manufactured by chemically modifying the naturally occurring amino acid phenylalanine. This sweetener can’t be used by people with phenylketonuria (a rare congenital disorder that disrupts the body’s ability to metabolize phenylalanine and can result in severe nerve damage). Despite extensive safety testing showing aspartame to be safe, its use has been implicated by the popular press in everything from headaches to loss of attentiveness. At this time, there is no scientific validity to these claims.

For the same reason that people have recently sought substitutes for fat, noncaloric sugar substitutes became popular in the 1960s as people began to try to control their weight. Sugar substitutes are of two basic types: intense sweeteners and sugar alcohols. Intense sweeteners are also called non-nutritive sweeteners, because they are so much sweeter than sugar that the small amounts needed to sweeten foods contribute virtually no calories to the foods. These sweeteners also do not promote tooth decay. Currently, four such intense sweeteners are available, both for use in processed foods and for home consumption. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has set “acceptable daily intakes” (ADI) for these sweeteners. The ADI is the amount that can be consumed daily over a lifetime without risk.

One of these sweeteners is aspartame (NutraSweet brand). It is manufactured by chemically modifying the naturally occurring amino acid phenylalanine. This sweetener can’t be used by people with phenylketonuria (a rare congenital disorder that disrupts the body’s ability to metabolize phenylalanine and can result in severe nerve damage). Despite extensive safety testing showing aspartame to be safe, its use has been implicated by the popular press in everything from headaches to loss of attentiveness. At this time, there is no scientific validity to these claims.

Aspartame is not heat stable, so it can’t be added to foods that will be cooked or baked, although it can be added to some foods (such as coffee) after heating. Saccharin, a second non-nutritive sweetener, was associated with cancer in mice when it was fed in very large amounts. However, further studies have found no links between saccharin and human cancer. This recently led the U.S. government to remove it from its list of potential cancer-causing chemicals. Although saccharin is heat stable, in some cases it cannot satisfactorily be used in baking because it lacks the bulk of sugar. Acesulfame K (Sunnett), a third intense sweetener, was approved by the FDA in 1998 for use in soft drinks, although it was used in various food products before that. About 200 times sweeter than sugar, this noncaloric product has been extensively tested for safety. After reviewing more than 90 studies, the FDA deemed the sweetener safe in amounts up to the equivalent of a 132-pound person consuming 143 pounds of sugar annually (an Acceptable Daily Intake of 15 milligrams per kilogram of body weight; 1 kilogram is about 2.2 pounds). Because it is not metabolized, acesulfame K can be used safely by people with diabetes. The sweetener is more heat stable than aspartame, maintaining its structure and flavor at oven temperatures more than 390° Fahrenheit and under a wide range of storage conditions. Like saccharin and aspartame, acesulfame K lacks bulk, so its use in home baking requires recipe modification. The flavor of acesulfame K has been described as clean and quickly perceptible, although disagreement exists about whether it leaves an aftertaste. A fourth intense sweetener, sucralose (Splenda), was approved by the FDA in 1998 for sale and use in commercial food products. Sucralose is made by chemically modifying sucrose (table sugar) to a non-nutritive, noncaloric powder that is about 600 times sweeter than sugar. Before approving sucralose, the FDA reviewed more than 110 research studies conducted in both human and animal subjects. It concluded that the sweetener is safe for consumption by adults, children, and pregnant and breastfeeding women in amounts equivalent to the consumption of about 48 pounds of sugar annually (an Acceptable Daily Intake of 5 milligrams per kilogram of body weight). People with diabetes may also safely consume the sweetener, because it is not metabolized like sugar. In addition, sucralose is highly stable to heat and so will not lose its sweetness when used in recipes that require prolonged exposure to high temperatures (such as baking) or when stored for long periods. The product is currently available in the form of a powdered sugar substitute and in some commercial baked goods, jams and jellies, sweet sauces and syrups, pastry fillings, condiments, processed fruits, fruit juice drinks, and beverages, and its use is approved for various additional products. However, use of sucralose in home baking is expected to be limited by its low bulk in comparison with table sugar. Foods containing intense sweeteners should not be given to infants or children, who need energy to grow and to sustain their high activity levels. Foods that contain intense sweeteners and lack any nutritive value also should not replace nutrient-dense foods in your diet. The sugar alcohols xylitol, mannitol, and sorbitol contain less than 4 calories per gram. These sugar alcohols are digested so slowly that most are simply eliminated. Unfortunately, excessive consumption can cause diarrhea or bloating in some people. So-called “natural” sweeteners provide the same number of calories as sugar and have acquired the reputation, albeit incorrectly, of being healthier than sugar, because they seem more natural than processed table sugar. These include honey, maple syrup and sugar, date sugar, molasses, and grape juice concentrate. In reality, these sweeteners contain no more vitamins or minerals than table sugar. Honey may harbor small amounts of the spores of the bacteria that produce botulism toxin and should never be given to babies younger than 1 year.

The Bottom Line on Carbohydrates

Carbohydrates-sugars and starches-are the main source of fuel for our bodies. When we choose carbohydrate-rich foods, our best bets are fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and legumes, because these foods are also rich sources of health-promoting vitamins, minerals, phytochemicals, and fiber. But like all calories, extra calories from carbohydrates beyond those we need to replenish the energy we burn are converted to fat and stored in our fat cells. Non-caloric sweeteners seem to be a safe alternative to sugar for most people, but the foods that contain them are often nutritionally empty and their use in home cooking is limited. The so-called natural sweeteners are no better for you than sugar.

The Bottom Line on Carbohydrates

Carbohydrates-sugars and starches-are the main source of fuel for our bodies. When we choose carbohydrate-rich foods, our best bets are fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and legumes, because these foods are also rich sources of health-promoting vitamins, minerals, phytochemicals, and fiber. But like all calories, extra calories from carbohydrates beyond those we need to replenish the energy we burn are converted to fat and stored in our fat cells. Non-caloric sweeteners seem to be a safe alternative to sugar for most people, but the foods that contain them are often nutritionally empty and their use in home cooking is limited. The so-called natural sweeteners are no better for you than sugar.

Contacts: lubopitno_bg@abv.bg www.encyclopedia.lubopitko-bg.com Corporation. All rights reserved.

DON'T FORGET - KNOWLEDGE IS EVERYTHING!