FATS

It’s difficult to read a newspaper or listen to the evening news without hearing something new about fat and its connection with disease. Diets that are high in fat are strongly associated with an increased prevalence of obesity and an increased risk of developing coronary artery disease, high blood pressure, diabetes mellitus, and certain types of cancer. Health authorities recommend that we reduce our total fat intake to about 30 percent of total calories. They also recommend that we limit our intake of saturated fat (the type of fat most often found in meat and dairy products) to less than 10 percent of our fat calories and try to be sure that the fat we do eat is mostly the monounsaturated or polyunsaturated type. These changes have been shown to decrease our risk for several diseases.

Fat as a Nutrient

Fat is an essential nutrient, because our bodies require small amounts of several fatty acids from foods (the so-called essential fatty acids) to build cell membranes and to make several indispensable hormones, namely, the steroid hormones testosterone, progesterone, and estrogen, and the hormone-like prostaglandins. Dietary fats also permit one group of vitamins, the fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, and K), to be absorbed from foods during the process of digestion. Fats help these vitamins to be transported through the blood to their destinations. The fat in our bodies also provides protective insulation and shock absorption for vital organs.

As a macronutrient, fat is a source of energy (calories). The fat in food supplies about 9 calories per gram, more than twice the number of calories as the same amount of protein or carbohydrate. As a result, high-fat foods are considered “calorie-dense” energy sources. Any dietary fat that is not used by the body for energy is stored in fat cells (adipocytes), the constituents of fat (adipose) tissue The Dietary Guidelines for Americans recommend that no more than 30 percent of our calories should come from fat, and only a third of that should be saturated fat.

Sorting Out the Fats

Our health is influenced by both the amount and the type of fat that we eat. Fats are molecules; they are classified according to the chemical structures of their component parts. But you don’t need to be a chemist to understand the connection between the various fats in foods and the effect these fats have on the risk for disease. Some definitions will help. Dietary fats, or triglycerides, are the fats in foods. They are molecules made of fatty acids (chain-like molecules of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen) linked in groups of three to a backbone called glycerol. When we eat foods that contain fat, the fatty acids are separated from their glycerol backbone during the process of digestion. Fatty acids are either saturated or unsaturated, terms that refer to the relative number of hydrogen atoms attached to a carbon chain. Fat in the foods that we eat is made up of mixtures of fatty acids-some fats may be mostly unsaturated, whereas others are mostly saturated.

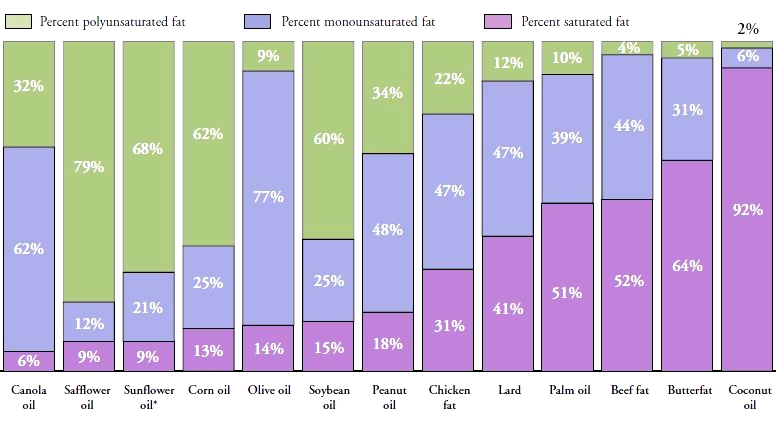

Monounsaturated fatty acids are fatty acids that lack one pair of hydrogen atoms on their carbon chain. Foods rich in monounsaturated fatty acids include canola, nut, and olive oils; they are liquid at room temperature. A diet that provides the primary source of fat as monounsaturated fat (frequently in the form of olive oil) and includes only small amounts of animal products has been linked to a lower risk of coronary artery disease. This type of diet is commonly eaten by people who live in the region surrounding the Mediterranean Sea.

Polyunsaturated fatty acids lack two or more pairs of hydrogen atoms on their carbon chain. Safflower, sunflower, sesame, corn, and soybean oil are among the sources of polyunsaturated fats (which are also liquid at room temperature). The essential fatty acids, linoleic and linolenic acid, are polyunsaturated fats.

A COMPARISON OF FATS

Like monounsaturated fats, polyunsaturated fats lower blood cholesterol levels and are an acceptable substitute for saturated fats in the diet. Saturated fatty acids, or saturated fats, consist of fatty acids that are “saturated” with hydrogen. These fats are found primarily in foods of animal origin-meat, poultry, dairy products, and eggs-and in coconut, palm, and palm kernel oil (often called “tropical oils”). Foods that are high in saturated fats are firm at room temperature. Because a high intake of saturated fats increases your risk of coronary artery disease, nutrition experts recommend that less than 10 percent of your calories should come from saturated fats.

Omega-3 fatty acids are a class of polyunsaturated fatty acids found in fish (tuna, mackerel, and salmon, in particular) and some plant oils such as canola (rapeseed) oil. These fatty acids have made the news because of the observation that people who frequently eat fish appear to be at lower risk for coronary artery disease. Omega-3 fatty acids also seem to play a role in your ability to fight infection.

Hydrogenated fats are the result of a process in which unsaturated fats are treated to make them solid and more stable at room temperature. The hydrogenation process, which involves the addition of hydrogen atoms, actually results in a saturated fat. Trans-fatty acids are created by hydrogenation.

Omega-3 fatty acids are a class of polyunsaturated fatty acids found in fish (tuna, mackerel, and salmon, in particular) and some plant oils such as canola (rapeseed) oil. These fatty acids have made the news because of the observation that people who frequently eat fish appear to be at lower risk for coronary artery disease. Omega-3 fatty acids also seem to play a role in your ability to fight infection.

Hydrogenated fats are the result of a process in which unsaturated fats are treated to make them solid and more stable at room temperature. The hydrogenation process, which involves the addition of hydrogen atoms, actually results in a saturated fat. Trans-fatty acids are created by hydrogenation.

An increase in consumption of these fats is a concern because they have been associated with an increased risk of coronary artery disease. Hydrogenated fat is a common ingredient in stick and tub margarine, commercial baked goods, snack foods, and other processed foods.

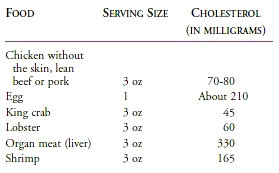

Cholesterol is a waxy, fat-like substance that is a necessary constituent of cell membranes and serves as a precursor for bile acids (essential for digestion), vitamin D, and an important group of hormones (the steroid hormones). Our livers can make virtually all of the cholesterol needed for these essential functions. Dietary cholesterol is found only in foods of animal origin, that is, meat, poultry, milk, butter, cheese, and eggs. Foods of plant origin, that is, fruits, vegetables, nuts, seeds, legumes, grains, and the oils derived from them, do not contain cholesterol. Eggs are the food most often associated with cholesterol, because the average large egg contains about 210 milligrams of cholesterol (only in the yolk), and the recommended daily cholesterol intake is 300 mg or less. However, for most people, meat contributes a higher proportion of cholesterol to the diet than do eggs, because cholesterol is found in both the lean and fat portions of meat. Shellfish have acquired an undeserved reputation for being high in cholesterol. Their cholesterol and total fat contents are actually comparatively low.

Cholesterol is a waxy, fat-like substance that is a necessary constituent of cell membranes and serves as a precursor for bile acids (essential for digestion), vitamin D, and an important group of hormones (the steroid hormones). Our livers can make virtually all of the cholesterol needed for these essential functions. Dietary cholesterol is found only in foods of animal origin, that is, meat, poultry, milk, butter, cheese, and eggs. Foods of plant origin, that is, fruits, vegetables, nuts, seeds, legumes, grains, and the oils derived from them, do not contain cholesterol. Eggs are the food most often associated with cholesterol, because the average large egg contains about 210 milligrams of cholesterol (only in the yolk), and the recommended daily cholesterol intake is 300 mg or less. However, for most people, meat contributes a higher proportion of cholesterol to the diet than do eggs, because cholesterol is found in both the lean and fat portions of meat. Shellfish have acquired an undeserved reputation for being high in cholesterol. Their cholesterol and total fat contents are actually comparatively low.

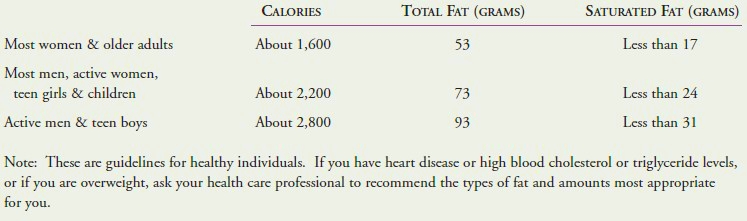

RECOMMENDED FAT INTAKE

Health experts recommend consuming no more than 30 percent of our calories from fat-with no more than 10 percent from saturated fat. Here is a chart to help you determine how much fat you should eat.

Health experts recommend consuming no more than 30 percent of our calories from fat-with no more than 10 percent from saturated fat. Here is a chart to help you determine how much fat you should eat.

Fat Substitutes

To appeal to our desire for lower-fat substitutes for our favorite high-fat foods, the commercial food industry has developed low- or lower-fat versions of many foods using various fat replacers. Until recently, fat replacers always consisted of proteins or carbohydrates, such as starches or gels, but the kinds of foods that could be prepared with these fat replacers were limited by their inability to withstand the high temperatures of frying. In 1996, after a long period of development, safety testing, and governmental review, the first non-caloric fat, olestra, was approved by the FDA for use in the manufacture of savory (non-sweet) snacks (such as crackers and chips). Because olestra is a modified fat, it is the first heat-resistant fat substitute, which allows it to be used to make fried foods. In addition, olestra gives foods the flavor and creamy “mouth feel” of high-fat foods. FDA approval of olestra was controversial for two reasons. First, this artificial ingredient, if approved and accepted,

would be the first in history to be consumed in quantities comparable to the quantities of fat, carbohydrates, and proteins we currently consume from food sources. In other words, these novel, previously unknown substances could become major parts of the diets of some people, and there would be no historical experience to tell us what the substances might do in our bodies. Some scientists predicted that the substance would cause serious gastrointestinal complaints despite controlled studies demonstrating its safety. However, in the first year of availability of olestracontaining foods, the predicted intestinal problems were not significant. Tests in which volunteers ate large quantities of olestra-containing potato chips or regular potato chips without knowing which type they were eating showed no differences in gastrointestinal complaints between the two groups. Second, tests of olestra showed that it inhibits the absorption of fat-soluble compounds (vitamins A, D, E, and K and some carotenoids) from foods eaten at the same time as the olestra-containing foods, whereas it has no effect on the absorption of other nutrients or on the body’s stores of fat-soluble vitamins. To compensate for this effect of olestra on fat-soluble vitamin absorption, foods prepared with olestra have small amounts of these vitamins added to them. At this writing, the range of foods that can include olestra as a fat substitute is quite narrow. Some questions do remain about the long-term safety of the product, although long-term studies in young, growing animals and several studies in humans have shown no negative effects.

How should you decide whether to include foods with fat replacers in your eating plan, and how much of these foods do you include? From a health standpoint, small amounts of olestra-containing foods appear to be harmless. But from a purely nutritional standpoint, most foods that contain fat replacers are snack foods essentially devoid of nutritional benefit. In addition, these foods are not caloriefree. Many remain high in calories, and some foods that contain carbohydrate fat replacers are even higher in calories than their higher-fat counterparts, so they are still caloriedense, nutritionally poor foods. It’s fine to choose small amounts of these foods occasionally, but better low-fat snack choices include fruits, vegetables, nonfat yogurt, and whole-grain pretzels and breads.

The Bottom Line on Fats

Dietary fat is a source of energy, but high-fat diets, especially diets high in saturated fat, increase the risk of gaining excessive amounts of weight and of developing diabetes, coronary artery disease, high blood pressure, and several types of cancer. This increased risk is the reason that health experts encourage us to reduce our intake of total and saturated fats by:

• increasing our intake of fruits, vegetables, and wholegrain foods, which are naturally low in fat, and preparing them with a minimum of added fats;

• consuming low-fat dairy products such as nonfat milk and yogurt and reduced-fat cheeses;

• limiting our intake of red meat, poultry, and fish to 5 to 7 ounces daily;

• choosing lean cuts of red meat and poultry, removing the skin before eating poultry, and preparing the meat with a method that uses little or no additional fats;

• choosing some fish that is high in omega-3 fatty acids and preparing it with little or no added fat.

To appeal to our desire for lower-fat substitutes for our favorite high-fat foods, the commercial food industry has developed low- or lower-fat versions of many foods using various fat replacers. Until recently, fat replacers always consisted of proteins or carbohydrates, such as starches or gels, but the kinds of foods that could be prepared with these fat replacers were limited by their inability to withstand the high temperatures of frying. In 1996, after a long period of development, safety testing, and governmental review, the first non-caloric fat, olestra, was approved by the FDA for use in the manufacture of savory (non-sweet) snacks (such as crackers and chips). Because olestra is a modified fat, it is the first heat-resistant fat substitute, which allows it to be used to make fried foods. In addition, olestra gives foods the flavor and creamy “mouth feel” of high-fat foods. FDA approval of olestra was controversial for two reasons. First, this artificial ingredient, if approved and accepted,

would be the first in history to be consumed in quantities comparable to the quantities of fat, carbohydrates, and proteins we currently consume from food sources. In other words, these novel, previously unknown substances could become major parts of the diets of some people, and there would be no historical experience to tell us what the substances might do in our bodies. Some scientists predicted that the substance would cause serious gastrointestinal complaints despite controlled studies demonstrating its safety. However, in the first year of availability of olestracontaining foods, the predicted intestinal problems were not significant. Tests in which volunteers ate large quantities of olestra-containing potato chips or regular potato chips without knowing which type they were eating showed no differences in gastrointestinal complaints between the two groups. Second, tests of olestra showed that it inhibits the absorption of fat-soluble compounds (vitamins A, D, E, and K and some carotenoids) from foods eaten at the same time as the olestra-containing foods, whereas it has no effect on the absorption of other nutrients or on the body’s stores of fat-soluble vitamins. To compensate for this effect of olestra on fat-soluble vitamin absorption, foods prepared with olestra have small amounts of these vitamins added to them. At this writing, the range of foods that can include olestra as a fat substitute is quite narrow. Some questions do remain about the long-term safety of the product, although long-term studies in young, growing animals and several studies in humans have shown no negative effects.

How should you decide whether to include foods with fat replacers in your eating plan, and how much of these foods do you include? From a health standpoint, small amounts of olestra-containing foods appear to be harmless. But from a purely nutritional standpoint, most foods that contain fat replacers are snack foods essentially devoid of nutritional benefit. In addition, these foods are not caloriefree. Many remain high in calories, and some foods that contain carbohydrate fat replacers are even higher in calories than their higher-fat counterparts, so they are still caloriedense, nutritionally poor foods. It’s fine to choose small amounts of these foods occasionally, but better low-fat snack choices include fruits, vegetables, nonfat yogurt, and whole-grain pretzels and breads.

The Bottom Line on Fats

Dietary fat is a source of energy, but high-fat diets, especially diets high in saturated fat, increase the risk of gaining excessive amounts of weight and of developing diabetes, coronary artery disease, high blood pressure, and several types of cancer. This increased risk is the reason that health experts encourage us to reduce our intake of total and saturated fats by:

• increasing our intake of fruits, vegetables, and wholegrain foods, which are naturally low in fat, and preparing them with a minimum of added fats;

• consuming low-fat dairy products such as nonfat milk and yogurt and reduced-fat cheeses;

• limiting our intake of red meat, poultry, and fish to 5 to 7 ounces daily;

• choosing lean cuts of red meat and poultry, removing the skin before eating poultry, and preparing the meat with a method that uses little or no additional fats;

• choosing some fish that is high in omega-3 fatty acids and preparing it with little or no added fat.

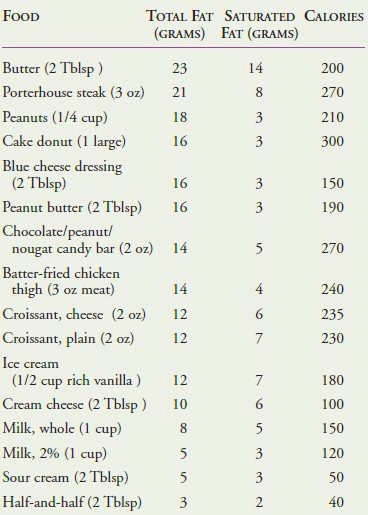

WHERE’S THE FAT?

Foods That May Pack More Fat Than You Think

Foods That May Pack More Fat Than You Think

CHOLESTEROL CONTENT OF FOODS

Cholesterol is found only in animal products. Below is a list of common foods and their cholesterol content.

Cholesterol is found only in animal products. Below is a list of common foods and their cholesterol content.

Contacts: lubopitno_bg@abv.bg www.encyclopedia.lubopitko-bg.com Corporation. All rights reserved.

DON'T FORGET - KNOWLEDGE IS EVERYTHING!